[Riceviamo e pubblichiamo. Roger Bromley, professore emerito della Nottingham University, che già aveva scritto per noi il meraviglioso Back home. Time, Memory and Football, ci ha inviato questo articolo sulla storia del Nottingham Forest FC e sui suoi legami con la figura di Giuseppe Garibaldi]

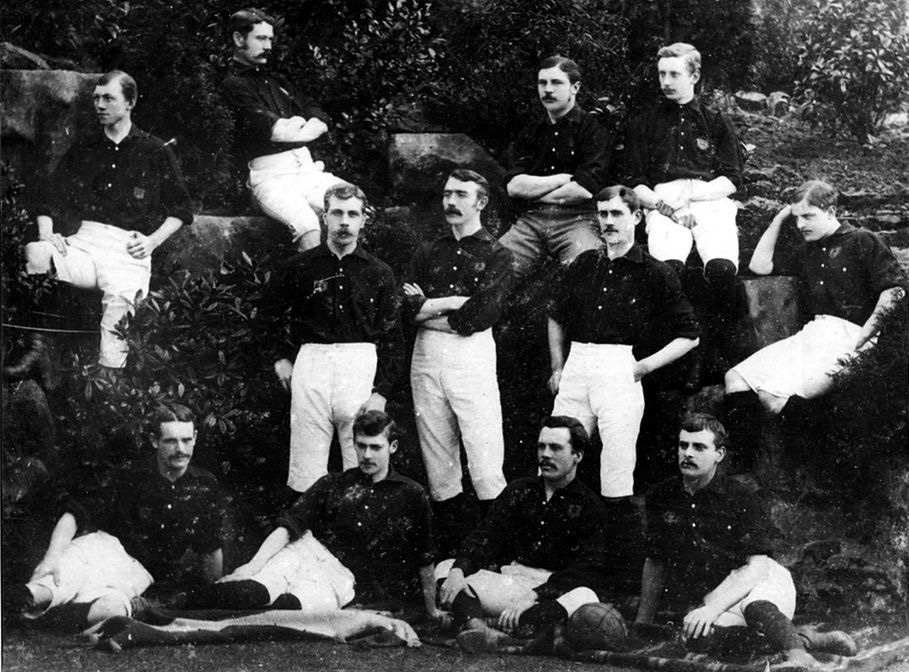

Nottingham Forest first team in 1884. Back Row – T. Danks, C.J. Caborn, S.W. Widdowson, T. Lindley. Middle Row – H. Billyeald, T. Hancock, F. Fox, A. Ward. Front Row – S. Norman, J.E. Leighton, F.W. Beardsley, G. Unwin.

Photo courtesy of Nottinghamshire County Library Service

di Roger Bromley

Ho vissuto a Nottingham per circa venti anni e durante questo periodo ho tifato Nottingham Forest. A volte, dopo prestazioni scarse della squadra, mi capitava di sentire i tifosi lasciare il campo borbottando «they’re not fit to wear the Garibaldi» [«non sono adatti a indossare la Garibaldi», NdT]. Questa frase ha continuato a intrigarmi per anni e, di recente, ho iniziato a cercare le origini della locuzione “the Garibaldi”. Che le maglie della squadra siano rosse costituisce un ovvio collegamento, ma mi chiedevo se fosse qualcosa di più che una semplice coincidenza. Le mie ricerche mi hanno portato indietro al 1865, anno in cui è stato fondato il Forest Football Club.

Una notizia del 1905 riporta «The Forest Club owed its existence to a number of active young fellows, many of whom are now well-known in the public life of Nottingham, who were accustomed to play the old-fashioned game of bandy on the Forest Recreation Ground» [«Il Forest deve la sua esistenza a una compagnia di giovani attivi, molti dei quali ora sono molto noti nella vita pubblica di Nottingham, che erano soliti praticare l’antico gioco del bandy sul Forest Recreation Ground», NdT]. Il “Bandy” detto anche “Shinney” o “Shinty” è un gioco di origini gaeliche con alcune somiglianze con l’hockey, le cui origini sono precedenti al cristianesimo. In Inghilterra era giocato in particolare da esuli scozzesi migrati al sud per lavoro o affari.

Quanti dei 15 membri fondatori fossero scozzesi non è certo anche se, con tre sole possibili eccezioni, i nomi non lasciano dubbi sulle loro origini. Si incontrarono al Clinton Arms Hotel (oggi The Orange Tree), all’angolo di Shakespeare Street diagonalmente opposto all’edificio dove D.H. Lawrence avrebbe studiato botanica nel primi anni venti del ventesimo secolo e dove, nel giugno del 1930, Albert Einstein avrebbe presentato le sue teorie sulla relatività nel Dipartimento di Fisica dell’allora University College di Notthingham.

Cosa abbia portato quel gruppo di giovani a mettere su una squadra di football è difficile da dire, forse la fondazione nel 1862 del Notts County e la presenza in quel club di Richard Daft, fratello di uno dei fondatori del Forest. Senza sorpresa la squadra giocò la sua prima partita contro il Notts County, nel marzo del 1866.

Il club fu chiamato “Forest” perché la squadra giocava all’ippodromo nel Forest Recreation Ground (un tempo parte della Foresta di Sherwood, casa di quell’altro ribelle leggendario chiamato Robin Hood), non lontano da Clinton Arms. Il comitato fondatore aveva stabilito una risoluzione secondo la quale i colori della squadra dovessero ispirarsi al “rosso garibaldi”, tributo al comandante italiano Giuseppe Garibaldi i cui soldati indossavano camice rosse. Non si tratta dunque soltanto di un collegamento casuale, ma un esplicita decisione formale e un omaggio.

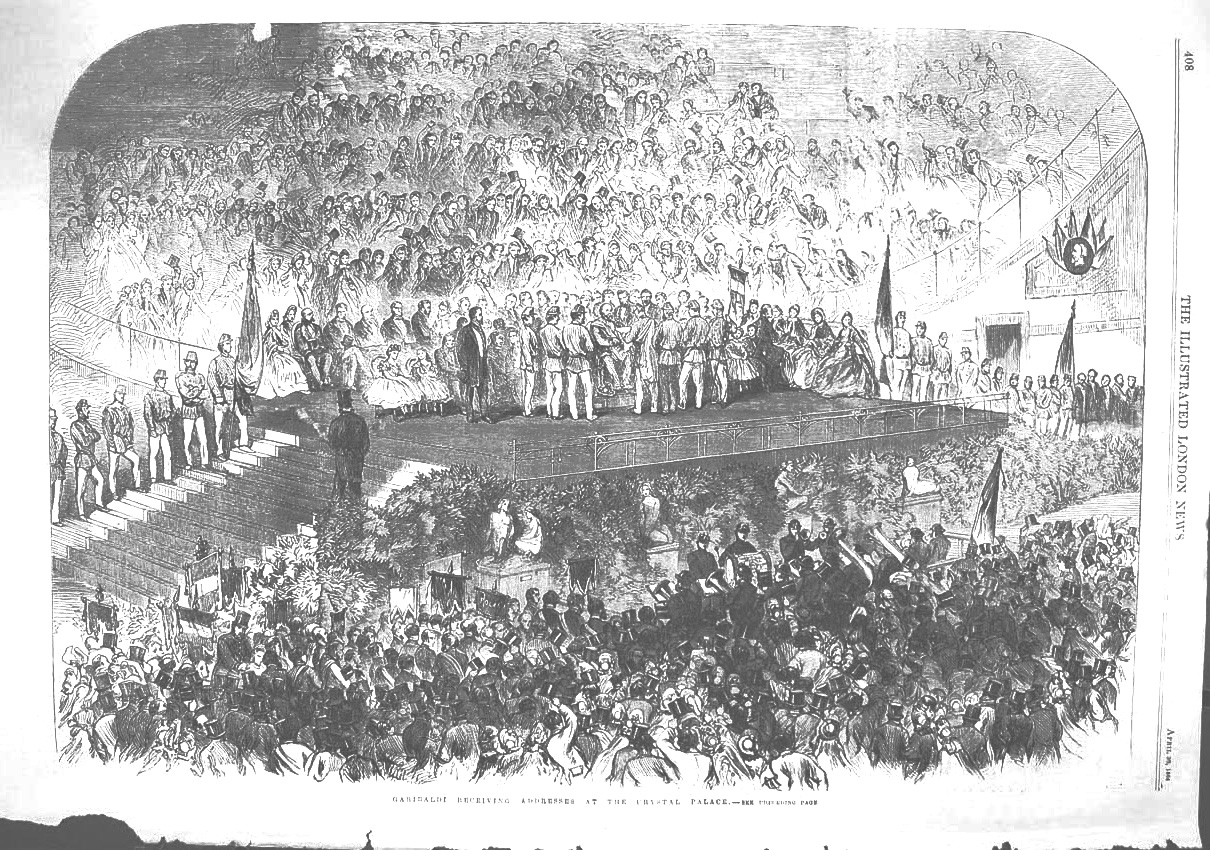

Garibaldi aveva visitato l’Inghilterra nell’aprile del 1864 ed era stato salutato da grandi folle ovunque si fosse recato. A Londra fu accolto anche da un corteo di associazioni di “Benefit, Temperance, Friendly and Trade” (associazionismo massonico tipico del mondo anglosassone nel XVIII sec., NdR) e azzarderei che la composizione dei membri fondatori del Forest Football Club sia stata simile: negozianti, piccoli imprenditori e membri della “aristocrazia del lavoro” o, al più, figli delle famiglie borghesi della citta. Non diversi, forse, dagli uomini di una generazione più anziana che formarono nel 1849 il Proprietary Bowling Green Club, circa un paio di centinaia di metri su per la strada da Clinton Arms (club di cui sono membro).

Più tardi designarono sé stessi come “gentiluomini dilettanti”, quando decisero di non entrare a far parte della Football League fondata nel 1888, che essi vedevano legata al professionismo (il club invero vi aderì nel 1891). Questa auto-definizione suggerisce l’appartenenza alla classe media. Garibaldi stesso aderiva alla massoneria e forse anche alcuni di questi uomini, o i loro padri. Non erano necessariamente radicali, ma è probabile che la camicia di Garibaldi fosse percepita allora come lo sarebbe stata la t-shirt di Che Guevera un centinaio di anni dopo o più, comunemente accettata senza problemi.

Tuttavia Feargus O’Connor, leader Cartista (un movimento politico inglese prevalentemente working class, il cui nome derivava dalla People’s Charter, la “Carta del Popolo”, NdT), era stato membro del Parlamento per la circoscrizione di Nottingham dal 1847 al 1852, il che suggerisce una forte presenza liberale e simpatie cartiste nel collegio elettorale (al tempo la working class non aveva diritto di voto). La sua statua oggi è situata a circa 300 metri da Clinton Arms.

Ispirato dall’immagine romantica dell’“eroe combattente” dell’Unificazione italiana, questa “compagnia di giovani attivi” (ognuno dei quali partecipava alle spese con un contributo mensile) ordinò una dozzina di divise con nappa di flanella rossa, da cui “Reds”, il coro che ancora echeggia sul campo durante le partite. Venti anni dopo due dei giocatori si trasferirono a Woolwich, e il club inviò loro un pallone e un set di uniformi rosse perché avevano fondato la squadra di lavoratori che un giorno sarebbe divenuta l’Arsenal, ancora oggi in campo con gli stessi colori del Forest. Non solo pioniere delle uniformi rosse, il Forest è accreditato anche per avere introdotto nel gioco i parastinchi (originariamente ricavati tagliando gambali da cricket) e il fischietto dell’arbitro (che aveva rimpiazzato una bandiera bianca).

Raccolta di cori dei tifosi del Nottingham FC

Quello che aveva avuto origine come sport della classe media evolse in passione della working class e, anche se forse non molti membri del club oggi dipingerebbero sé stessi come “garibaldini”, tra i tifosi è ancora prevalente la presenza della classe lavoratrice in una città considerata roccaforte del Labour Party. Il precedente proprietario della squadra era un finanziatore del partito e il suo leggendario allenatore Brian Clough era un socialista che aveva attivamente supportato (e finanziato) i minatori locali nello sciopero del 1984/85.

Oggi, sotto la proprietà del miliardario kuwaitiano (Fawaz Mubarak Al-Hasawi, NdR), la “Garibaldi” continua a esistere solo come brand del marketing – nelle forme della Garibaldi Room (una sala conferenze) o della “Garibaldi Golden Goal Gamble”, una sfida a premi per i tifosi allo stadio che da poco si tiene alla fine del primo tempo delle partite casalinghe.

Nondimeno alcuni blog mantengono accesa la fiamma di Garibaldi e la primissima presenza su web si deve al sito “The Unofficial Nottingham Forest Football Club Home Page”, creata da due tecnici informatici della Nottingham University che hanno scelto il nome di “Garibaldi Reds”.

Retrocesso dalla Premier League alla fine del secolo scorso, oggi il Forest gioca in Championship (seconda serie inglese, NdT), ma i tifosi più anziani ancora serbano i ricordi dell’“era di Clough” e delle due Coppe dei Campioni consecutive vinte nel 1979 e nel 1980. Se la fortuna dovesse cambiare e il club tornare alla Champions’ o all’Europa League, gli spettatori italiani potranno alzare un bicchiere alla vista della “Garibaldi” tornata al suo posto e parte anche della loro storia.

[Traduzione Christo xho Presutti, l’originale in inglese segue in basso]

__

Roger Bromley è esperto di Cultural Studies, professore emerito in studi sociali alla Nottingham University (Emeritus Professor of Cultural Studies e Honorary Professor of Sociology), Visiting Professor della University of Lancaster, Associate Fellow alla Rhodes University, SA.

Durante la sua lunga carriera accademica ha effettuato ricerche in diversi ambiti e su diversi argomenti. Le pubblicazioni recenti includono un film documentario sul Rwanda, analisi del Sud Africa post apartheid, studi sul cinema of displacement e sulle forme di cultura pubblica e comunità.

In una delle email che ci ha scritto c’è una frase meravigliosa che riportiamo in originale:

«Everything I write is political and always has been, otherwise I see no point in bothering. This ‘football’ piece is only indirectly political but is the beginning of an auto-ethnography which will be a blend of sociological, political and cultural analysis, although at times it will be painful to write».

Su questo blog di Roger Bromley puoi leggere anche Back home. Time, Memory and Football.

__

Original in english

Robin Hood meets Garibaldi

by Roger Bromley

I have lived in Nottingham for almost twenty years and during this time I have supported Nottingham Forest. On occasion, after a particularly poor performance by the team, I would hear older supporters muttering as they left the ground, ‘they’re not fit to wear the Garibaldi’. This has continued to intrigue me over the years and, recently, I have started searching for the origin of ‘the Garibaldi’. The fact the team’s shirts are red is an obvious link but I wondered if it was more than just this coincidence. My searches have taken me back to 1865 when the (then) Forest football club was formed.

According to a report in 1905, ‘The Forest Club owed its existence to a number of active young fellows, many of whom are now well-known in the public life of Nottingham, who were accustomed to play the old-fashioned game of bandy on the Forest Recreation Ground’ (The Book of Football, 1997: p.222). ‘Bandy’ or ‘Shinney’ (Shinty) was a game with some similarities to hockey and of Gaelic origin, with its roots in pre-Christian times. In England, it was mainly played by Scottish ‘exiles’ who had moved south for work or business.

How many of the 15 founder members were Scottish is not known as, with three possible exceptions, their names give no clue as to their backgrounds. The men met at the Clinton Arms Hotel (now The Orange Tree) on the corner of Shakespeare Street, diagonally opposite the building where D.H Lawrence was to study Botany in the early years of the twentieth century and where, in June 1930, Albert Einstein was to lecture on his new theories of relativity in the Physics department of the then University College, Nottingham.

Why a group of young men should decide to set up a football team it is hard to say, except that the establishment of Notts County in the city in 1862, and the presence in the club of Richard Daft, a brother of one of the Forest founders, may well have acted as an incentive. Not surprisingly, the team’s first match took place against Notts County in March, 1866.

The club was called ‘Forest’ because the team played at the racecourse on the Forest Recreation Ground (once part of Sherwood Forest, home of that other legendary rebel, Robin Hood), not far from the Clinton Arms. The founding committee passed a resolution that the team colours should be ‘Garibaldi red’, a tribute to the Italian leader, Giuseppe Garibaldi whose followers wore red tunics. So, it was not just a casual link between the colour of the shirt and Garibaldi but an explicit, and formal, decision and homage.

Garibaldi had visited England in April, 1864 and was greeted by huge crowds wherever he went. In London, his reception included a procession of Benefit, Temperance, Friendly and Trade associations and I would hazard a guess that the composition of the founding members of Forest Football Club may have been similar: shopkeepers, small businessmen, and members of the ‘aristocracy of labour’ or, at least, the sons of the city’s ‘burgesses’ (borghese). Not unlike, perhaps, the men of an older generation who formed the Proprietary Bowling Green Club, a couple of hundred metres or so up the road from the Clinton Arms, in 1849 (a club of which I am a member).

They later styled themselves as ‘gentlemen amateurs’ when declining to join the Football League on its founding in 1888 as it was seen as linked with professionalism (the club actually joined in 1891). This self-ascription suggests a middle/lower middle class belonging. Garibaldi was a freemason and some of these men, or their fathers, may also have been. They would not necessarily have been radicals but perhaps the ‘Garibaldi’ shirt then was something like the Che Guevara tee-shirts a hundred years or more later, safely incorporated.

However, Feargus O’Connor, the Chartist leader, was the member of parliament for Nottingham from 1847 to 1852 which suggests, at least, a strong liberal presence and Chartist sympathies in the constituency (the working-class had no vote at that time). His statue today is about 300 metres from the Clinton Arms.

Inspired by the romantic image of the ‘warrior hero’ of Italian Unification, these ‘active young fellows’ ordered a dozen red-flannel caps with tassels for the players (each of whom agreed to pay a monthly subscription), hence the ‘Reds’, the cry which still echoes round the ground on match days. The treasurer bought the caps from the drapery store of C.F. Daft, one of the players. Twenty years later, when two of the players moved to work at Woolwich, the club sent a ball and a set of red shirts to the two men who established a works team which was later to become Arsenal who still play in the same colours as Forest.

Not only did Forest pioneer the red shirts but they are also credited with introducing shin guards (originally cut down cricket pads) and the referee’s whistle (which replaced the white flag) into the game.

What began as a middle class sport developed into a working-class passion and, while not many in the club today would perhaps see themselves as ‘garibaldinis’, its following is still predominantly working-class in a city which is a Labour Party stronghold. The club’s previous owner was a Labour Party supporter and donor and its legendary manager, Brian Clough, was a socialist who actively supported (and financed) local miners in the Miners’ Strike of 1984-5.

Today, under the ownership of its billionaire Kuwaiti owners, the ‘Garibaldi’ only lives on officially as a marketing brand – in the form of the Garibaldi Room (a conference suite) and the, short-lived, ‘Garibaldi Golden Goal Gamble’, a half-time goal-scoring challenge for supporters, with prizes. Nevertheless, bloggers keep the Garibaldi flame burning and the first ever presence on the web was a site called ‘The Unofficial Nottingham Forest Football Club Home Page’ set up by two IT technicians at the University of Nottingham and labelled ‘The Garibaldi Reds’.

Relegated from the Premier League at the end of the last century, today ‘Forest’ play in the the second tier, the Championship, but older supporters still cherish memories of the two successive European Cup victories in 1979 and 1980 and the ‘Clough era’. If fortunes change and once again the club appears in the Champions’ league or the Europa Cup, Italian viewers can raise a glass at the sight of the ‘Garibaldi’ back again in its rightful place as part of their history.

Pingback: Robin Hood meets Garibaldi | Casciavit FC

Pingback: Il Nottingham Forest e la leggenda di Brian Clough | Orange Stings

Ho vissuto per 6 mesi a Nottingham e non lo sapevo. Anzi, credevo che la prima divisa fosse come quella della Juve e la seconda Rossa. Sapevo che la Juve era bianconera perché loro gli mandarono a suo tempo le divise, e per loro la Juve, stranamente è molto spesso anche una seconda squadra da tifare.

Clough è un personaggio meraviglioso, però la Nottigham attuale non è un oasi socialista e progressista, anzi. Devo essere sincero e nella mia esperienza in UK Nottingham è stato l’unico luogo in cui sono stato vittima di razzismo e parlando ad aesempio con alcuni commercianti non british in città si respira un forte vento razzista. non si sa se sia dovuto alla sistuazione economica, ma rispetto a Londra si nota un numero bassisimo di persone di colore e un’invasione di Cinesi. La città sarà almeno per un terzo popolata da Cinesi di tutte le età. Le università, ve ne sono diverse e tutte importanti, hanno rapporti diretti con Cina per cui vi sono fittisimi scambi di studenti:

Fa un effettoi davvero strano, ma le cosidette classi che acmpano di benefit li sono per lo più composte da bianchi british il cui aspetto è molto simile al Badgby di Trainspotting, ubriachie violenti.

E la cosa triste è che il Forrest e i suoi tifosi, forse perché hanno smarrito questa identità “rossa” oramai vivono l’anno solo per la spicciola rivalità con i vicini di Leicester