Di seguito la seconda parte del racconto che Anthony Cartwright ha scritto per Fútbologia. È disponibile la prima parte con una breve introduzione di Christo Presutti.

Il testo originale inglese segue in calce, come anche una breve nota biografica sull’autore.

Ruggine e Ritorno

Parte 2 / 2

di Anthony Cartwright

traduzione di Sarah Cuminetti

revisione di Luca Wu Ming 3 e Christiano Presutti

Secondo tempo

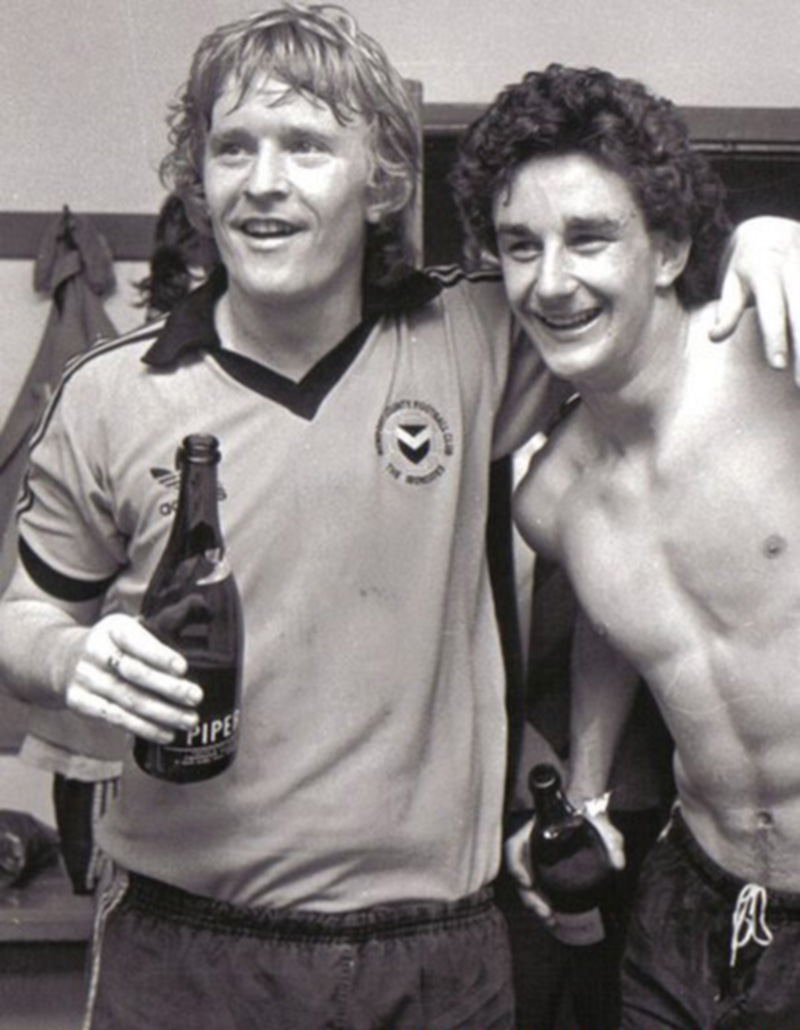

Tommy Tynan era il motivo principale per il quale seguivo la stagione del Newport con trasporto. Era grazie a lui che la squadra si era ritrovata a giocare in Germania Est. Penso sia stata l’allitterazione nel suo nome che aveva inizialmente attirato la mia attenzione. Uno dei miei eroi quell’anno era Roy Race, quel Roy of the Rovers le cui gesta nei Melchester Rovers venivano narrate in un fumetto settimanale. Si dà il caso che Tommy Tynan assomigliasse proprio a Roy dei Rovers, con quei capelli biondi che scendevano fino al collo, e il motivo per cui era diventato calciatore era una storia da un eroe dei fumetti. La sua carriera era cominciata nel Liverpool di Bill Shankly quando il quotidiano locale, il Liverpool Echo, aveva lanciato un concorso per trovare un nuovo giocatore.

Tynan non giocò mai nella prima squadra del Liverpool, ma finì per segnare circa un goal ogni due partite quando era al Newport e al Plymouth Argyle. (L’altra punta del Newport, John Aldridge, passò invece poi al Liverpool. Aldridge era infortunato all’epoca delle partite contro il Carl Zeiss Jena.) In area di rigore Tommy Tynan aveva il quid che hanno tutti i grandi giocatori: la capacità di piegare tempo e spazio a suo piacimento.

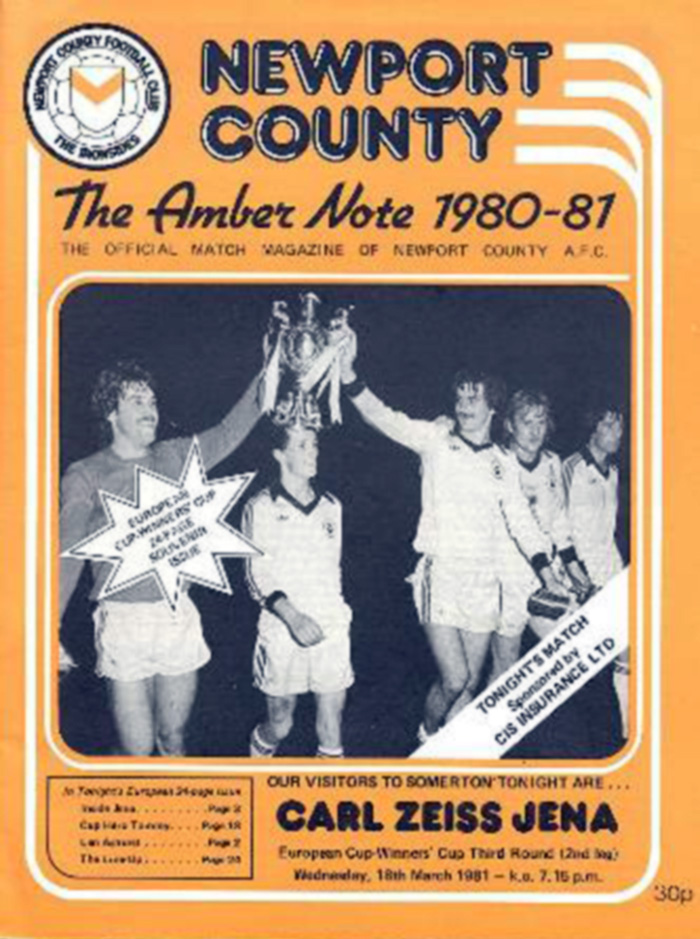

Anche il Carl Zeiss Jena era una squadra fondata da operai. La fabbrica di componenti ottici Carl Zeiss produceva microscopi, mirini per fucili, obbiettivi per fotocamere. Come detentori del titolo della Germania Est, erano grandi favoriti contro il Newport. Una visita oltre la cortina di ferro era un’avventura esaltante, avvolta nelle nebbie della Guerra Fredda. A fare da sottofondo ai commenti radiofonici che arrivavano da luoghi come Jena e Sofia e Tiblisi pareva esserci il suono costante delle pulsazioni analogiche di grandi oceani; con altre voci – russo, tedesco – che arrivavano indistinte, sepolte da qualche parte sotto la voce della BBC.

Cartoline di reti segnate in un paese che non esiste più #2

Ultimo minuto.

Arriva un traversone dalla destra, viene ribattuto. Gli attaccanti continuano a correre, i difensori con loro, così quando la palla è ributtata in mezzo, lanciando una rete potresti catturare una dozzina di giocatori.

La palla scivola verso Tynan che si posiziona per proteggerla, la controlla con un tocco leggero di collo destro e si apre uno spazio e un tempo là dove non c’è né l’uno né l’altro.

Si gira e calcia un tiro basso che supera la mano destra del portiere e finisce in rete.

Highlights della partita di Coppa delle Coppe Newport County – Carl Zeiss Jena, 1981

Allora come oggi, un pareggio 2 a 2 in trasferta in Europa ti metteva in posizione di vantaggio per la partita di ritorno, in virtù della regola dei goal fuori casa. L’altro giorno ho riguardato gli highlights del match di ritorno, quello giocato a Newport, e mentre mi concentravo ho visto i fanali delle auto che passavano nel buio oltre gli angoli vuoti del campo di Somerton Park, che procedevano – ci giurerei – su Tipton Road a Dudley, attraverso una città non ancora trasfigurata dai disastri degli anni a venire.

Il Newport passò in svantaggio quella sera, ma poi guadagnò corner su corner, martellando cross su cross. Nel primo tempo i difensori dello Jena respinsero la palle tre volte sulla linea di porta. Il pubblico ruggiva e si sporgeva oltre i bassi muretti di mattoni, così vicino al campo, sopra cartelloni che ripetevano ossessivamente la parola acciaio, come per accerchiare i tedeschi.

Ad un certo punto, ai venti metri Tynan vince un contrasto aereo sul suo marcatore, gli va via e scatta sul lato sinistro dell’area. Quando il compagno chiude il triangolo, il pallone ha uno strano rimbalzo, lui lo lascia scorrere e lo colpisce al volo di sinistro, entrambi i piedi staccati da terra. La palla si alza e poi si abbassa maligna, e sbatte contro la traversa per poi tornare in campo.

Fino all’ultimo secondo sembra che il goal stia per arrivare. L’ultimo tocco della partita è praticamente quello del portiere dello Jena che sfiora con la punta delle dita un colpo di testa e devia la palla appena sopra la traversa.

Con il senno di poi è facile chiedersi cosa sarebbe successo se una qualsiasi di quelle palle goal fosse entrata in rete quella sera. Lo Jena vinse contro il Benfica nel turno successivo – con meno fatica rispetto alla partita contro il Newport – e perse in finale contro la Dynamo Tiblisi. Non è da escludere che il Newport avrebbe potuto vincere la coppa. Ci rimasi molto male quando persero, ma ero fiducioso che sarebbero tornati. Pensavo che fossero una forza emergente del calcio della Black Country, anche se venivano dal Galles Meridionale.

Il resto degli anni ottanta furono una catastrofe.

La caduta libera del Newport County seguì un cammino comune a molte altre squadre. A Dudley il campo che avevo allegramente confuso con il Somerton Park del Newport crollò una mattina sprofondando in una miniera di calcare in disuso che aveva creato delle enormi caverne sotterranee. Ad essere precisi, questo fu ciò che accadde al campo di cricket proprio accanto, ma fu chiuso l’accesso a tutta la zona. In quei luoghi non si giocò mai più a calcio.

Erano gli stessi anni in cui la rivoluzione di Margaret Thatcher strinse la morsa sulla working class britannica – le acciaierie, le miniere, i cantieri navali – tutti decimati. Lei voleva chiudere tutto, la gente fuori dai piedi. Intere città arrugginirono. I Wolves sprofondarono giù dalla Prima Divisione fino alla Quarta, finirono quasi fuori dai giochi. Per un lungo periodo rimase aperta solo una gradinata che giaceva di sbieco al campo sotto la pioggia della Black Country.

Il Newport County fece una fine ancora peggiore. Furono retrocessi dalla Football League nel 1988 e l’anno successivo, l’Anno Zero del calcio inglese, cessarono del tutto di esistere. Due mesi prima del disastro di Hillsborough – dove era presente una delle sue stelle di un tempo, John Aldridge, che militava nel Liverpool – il tribunale dichiarò il fallimento del Newport, che non finì neanche la stagione della Conference (divisione dilettanti del calcio inglese). Ho citato Hillsborough perché mi pare rappresenti perfettamente la fine di quel “decennio infimo e disonesto”, per utilizzare la frase con cui W. H. Auden descrisse gli anni trenta. I fan di una città (Liverpool) decimata dalla Thatcher furono schiacciati a morte in una città analoga (Sheffield), mentre la sua polizia, che aveva lottato con tanto fervore contro i minatori, guardava dall’altra parte.

Tempi Supplementari

Per loro natura, le resurrezioni avvengono nelle circostanze più ostili. Quattro mesi dopo la liquidazione, 400 fan della vecchia squadra crearono a Newport un nuovo club. Per motivi legali, il nome era leggermente diverso, Newport A.F.C. Poterono ricominciare a usare il termine County soltanto a partire dal 1999.

La vita del Newport riprese dagli scalini più bassi del calcio professionistico. Come se non bastasse, per una stagione furono costretti a giocare tutte le partite in casa a una distanza siderale, nel paesino di Moreton-in-Marsh nel English Cotswold. Più tardi, dopo la metà degli anni novanta, dovettero anche giocare per due anni in Inghilterra, a Gloucester. Oggi lo stemma della squadra riporta ancora la dicitura “Exiles”, esiliati, in memoria di quei giorni (e, almeno a mio parere, nel ricordo di quei lavoratori della Black Country che si trasferirono nel Galles Occidentale nel 1912).

Eppure a venticinque anni e quattro promozioni dal loro esilio dalla Football League, sono tornati. A maggio hanno vinto contro un altro club gallese, il Wrexham, nella finale dei play-off della Conference League a Wembley. Questo fatto meriterebbe una storia a sé. Anche il Wrexham hauna storia di tutto rispetto, e a un livello ben più alto, uno dei club che hanno dato vita al calcio nel Galles, un’altra città che ha visto giorni decisamente migliori.

E mentre il County era via, il declino industriale è continuato. La maggior parte delle industrie di Newport sono sparite. Come la maggior parte delle città britanniche della working class operaia – comprese Dudley, Wolverhampton e Wrexham – non è rimasto molto oltre la ruggine.

Il Dudley Town milita nella West Midlands Regional League. Sembrano essere esistiti in uno stato di esilio permanente, condividendo il campo con quello di squadre vicine. Il fatto che siano ancora lì è probabilmente un miracolo bello e buono. L’ultima volta che li ho visti giocare è stato vent’anni fa o quasi, l’anno che ho lasciato Dudley. Giocavano sul campo del Round Oak Steelworks. Le acciaierie da cui prendono il nome chiusero nei primi anni ottanta, come era facile aspettarsi. Il club oggi almeno ha una sede stabile, presso il campo di atletica in fondo alla strada dove un tempo era la fabbrica. C’è una frase che uso nel mio romanzo Heartland pronunciata da un ex calciatore, ex operaio delle acciaierie, un uomo che sente di essere stato spinto ai margini della sua terra: we’re still here [«noi siamo ancora qui», NdT].

Anche i Wolves hanno avuto la loro resurrezione dopo i tempi bui degli anni ottanta, sulla scia dei goal segnati dall’eroe locale, Steve Bull. Hanno giocato alcune stagioni nella Premier League. Molineux è diventato un campo di calcio moderno, più piccolo rispetto ai giorni di gloria del club negli anni cinquanta, ma decisamente troppo grande per la First Division (la “Lega Pro” del calcio inglese, NdR) in cui giocheranno la prossima stagione (dopo varie retrocessioni, ora si trovano appena una divisione davanti al Newport).

Tommy Tynan fa il taxista a Plymouth, scrive una rubrica sul calcio per il quotidiano locale. A Jena la fabbrica Carl Zeiss esiste ancora, ma la nazione che la squadra rappresentava non esiste più. Il 1989 è stato anche l’anno in cui la Germania dell’Est è implosa. La stagione 80-81 fu la migliore della storia del Carl Zeiss Jena, che raggiunse l’apice del successo arrivando in finale contro il Tiblisi. Ora la squadra gioca in una divisione regionale tedesca.

Il 13 luglio 2013 il Newport County è tornato a Jena ancora una volta, per un’amichevole pre-campionato, le squadre sono completamente cambiate, ma grandi speranze sono riposte nella stagione a venire.

__

Original in english by Anthony Cartwright. The first part is available here.

Rust and Return

Parte 2 / 2

di Anthony Cartwright

Second Half

Tommy Tynan was the main reason I was following Newport’s season so closely. He was the reason they were in East Germany at all. I think it was the alliteration of his name that made me pay attention at first. One of my other heroes that year was Roy Race, Roy of the Rovers, whose matches for Melchester Rovers were reported in a weekly comic. It turned out that Tommy Tynan even looked like Roy of the Rovers, with his blond hair that fell onto his collar, and the reason he was a footballer at all was like something from a comic-book. His career had started at Bill Shankly’s Liverpool when the city’s newspaper, the Liverpool Echo, ran a talent competition to find a new player.

Tynan never played in the Liverpool first team, but went on to score more or less a goal every other game in his seasons with Newport and Plymouth Argyle. (His strike partner at Newport, John Aldridge, did go on to play for Liverpool. Aldridge was injured for the Carl Zeiss Jena matches.) In the penalty area Tommy Tynan had that thing that all the best players have: the ability to bend time and space to their own will.

Carl Zeiss Jena were also a team founded by industrial workers. The Carl Zeiss optics plant made microscopes, rifle sites, camera lenses. As East German cup-winners, they were big favourites to beat Newport. A visit behind the iron curtain was something exciting, the fog of the Cold War lingered around it. The radio commentary that came back from places like Jena and Sofia and Tiblisi always seemed to have the sound of great oceans seething beyond it in an analogue throb; and other voices – Russian, German – came muffled, buried somewhere beneath the voice of the BBC.

Cartoline di reti segnate in un paese che non esiste più #2

Last minute.

A cross comes in from the right, is half cleared. The runners keep going, the defenders with them, so when the ball is zipped back in you could throw a goal net over a dozen players.

The ball skids towards Tynan who shapes as if to shield it, takes a touch with his right instep which gives him time and space where there is none at all.

He turns and hits it low past the keeper’s right hand into the net.

Then, as now, a two-all draw away in Europe put you in control of the home leg because of the away goals rule. I watched back the highlights of the second leg, the match in Newport, the other day, and as I concentrated, the car headlights that moved through the dark behind the unfilled corners of the Somerton Park ground were driving, I swear, along Tipton Road in Dudley, through a town not yet transfigured by the disasters of the intervening years.

Newport went a goal down that night but then won corner after corner, thumped in cross after cross. Jena defenders cleared the ball off the line three times in the first-half. The crowd roared and leaned over the low brick walls, so close to the pitch, over hoardings which had the word steel repeated over and over, hemming the German side in.

At one point, Tynan wins a flick-on twenty-five yards out, spins away from his marker and sprints towards the left hand side of the box. When the return ball comes to him it bounces awkwardly and he lets it run across his body, hits it as a volley with his left foot, both feet off the floor. The ball rises, dips viciously, and crashes off the bar back into play.

It feels like a goal is coming right until the dying seconds. Pretty much the last touch of the match is from the Jena keeper, who gets his fingertips to a header, pushes the ball just over the bar.

With hindsight, it’s easy to wonder what might have happened if any of those chances had gone in that night. Jena beat Benfica in the next round – more comfortably than they had defeated Newport – and lost to Dynamo Tiblisi in the final. It is not out of the question that Newport could have won the whole competition. I was upset when they lost, but was confident they’d be back. I thought they were a coming force of Black Country football, even if they were from South Wales.

The rest of the nineteen-eighties were a catastrophe.

Newport County’s freefall happened at the same time as plenty of others. In Dudley, the ground I’d happily mistaken for Newport’s Somerton Park, collapsed one morning into disused limestone workings that formed great caverns underneath it. To be more accurate, this is what happened to the cricket ground next door, but the whole area was sealed off. Football was never played there again.

These were the years when Margaret Thatcher’s revolution took its grip on the British working classes – the steel works, the mines, the shipyards – were decimated. She wanted them shut, the people out of the way. Whole towns rusted. Wolves went from the First Division right down to the Fourth and almost out of business completely. For a long spell they only had one functioning stand which sat skewed at an angle from the pitch in the Black Country rain.

Newport County fell hardest of all. They were relegated from the Football League in 1988 and the following year, English football’s Year Zero, they went out of existence completely. Two months before the Hillsborough disaster – at which one of their ex-stars John Aldridge was present as a Liverpool player – Newport were wound up by the courts and couldn’t even finish their season in the Conference (English football’s fifth tier). I mention Hillsborough here because it seems to me to represent everything about the end of that “low and dishonest decade”, to use the phrase with which W.H.Auden’s described the nineteen-thirties. Fans from one city (Liverpool) decimated by Thatcher were crushed to death in another (Sheffield), while her police force, who had fought the miners so enthusiastically, looked the other way.

Extra Time

By their nature, resurrections happen in the direst circumstances. Four months after their liquidation, a football club was re-constituted in Newport by 400 of the old club’s fans. For legal reasons, they had the slightly different title of Newport A.F.C. They were able to use the name County again in 1999.

Newport had to start life again in the lowest reaches of senior football. Added to that, for a season they had to play home games a whole world away, in the English Cotswold village of Moreton-in-Marsh. They were forced to spend another two years playing in England, in Gloucester, later in the ‘nineties. Today the club’s badge still has the word Exiles printed on it as a reminder of that time (and, in my mind at least, a nod to those Black Country workers who moved to South Wales in 1912).

Yet twenty-five years and four promotions after their exile from the Football League, they have returned. In May they beat another Welsh club, Wrexham, in the Conference Play-Off Final at Wembley. This is a story in itself. Wrexham are another club with a proud history at a higher level, a founding club of football in Wales, another town that has seen much better days.

And while County were away, the industrial decline continued. Most of Newport’s industry has gone. Like most other British industrial working-class towns – Dudley, Wolverhampton and Wrexham included – so much of it has rusted away.

Dudley Town play in the West Midlands Regional League. They seem to have existed in permanent exile, sharing the grounds of clubs nearby. It’s probably a miracle they’re there at all. The last time I watched them play was twenty years ago or so, the year I left Dudley. They were using the ground of the Round Oak steelworks. The works themselves had shut in the early-eighties, of course. The club have a permanent home now, at least, at the athletics ground down the road from where the steelworks used to be. There’s a line I use in my novel Heartland from an ex-footballer, ex-steelworker, a man who feels he’s been pushed to his country’s margins: we’re still here.

Wolves had their own resurrection after the dark days of the eighties, driven by the goals of local hero, Steve Bull. They’ve had seasons in the Premier League. Molineux has been transformed into a modern football ground, smaller than in the club’s 1950s glory days, but much too big for the First Division (England’s third level) that they will play in next season (after successive relegations, they are now only one division above Newport).

Tommy Tynan drives a taxi in Plymouth, writes a football column for the local paper. The Carl Zeiss works continues in Jena, but the country the club represented no longer exists. 1989 was also the year that East Germany imploded. The 80-81 season was the finest in Carl Zeiss Jena’s history, reaching that final against Tiblisi their greatest achievement. The club now plays in a German regional league.

On July 13th 2013, Newport County travel to Jena once again, for a pre-season friendly, the clubs changed beyond measure, but full of hope for the season to come.

__

Anthony Cartwright è uno scrittore inglese.

Ha scritto i romanzi “The Afterglow”, “Heartland” e “How I Killed Margaret Thatcher”.

Dei tre, in italiano è disponibile “Heartland”, 66thAnd2nd 2013, «inquietante radiografia dell’Inghilterra multietnica d’inizio millennio, tramortita dalla cura Thatcher, ingannata dal New Labour di Blair e coinvolta nel conflitto a bassa intensità che dilaga nelle cinture metropolitane smarrite e abbandonate a sé stesse». [dal sito dell’editore, NdR]

Puoi trovare il libro anche nella libreria Anobii di Fútbologia.

Ciao,

volevo segnalarvi che manca un pezzo dell’originale, quello subito prima del last minute.

Grazie e buon lavoro

Saverio

Ciao,

in realtà per sbaglio era stato ripetuto l’incipit della parte 1.

Corretto.

Grazie mille.

C_